Opinion in lead

Has Nepal finally broken out of its trend of export stagnation?

Nepal’s Prime Minister’s Office recently unveiled the progress report of the current Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli’s three-year reign. Among many achievements highlighted, the document emphasized an increase in export. The progress report points out that export in the first six months of the current fiscal year 2020/2021 has increased by 6.1 percent. Likewise, it also points out an overall increase in exports by 4.5 percent in the period ruled by the current government (since mid-February 2018). While a brake applied to the ever cruising trade deficit is undoubtedly a relief, when one scratches the surface, much of the optimism is lost.

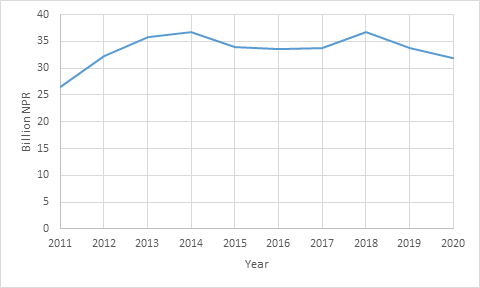

Nepal’s export has seen a clear stagnation in the period 2014–2018—the total export in 2018 was less than the total export in 2014 (Figure 1). We also see that Nepal’s total export has undoubtedly surged in the period 2018–2020. While total export has declined in 2019 relative to 2020, the decline could very well have been because of restrictions and disruptions caused by COVID-19. But once we go beyond the mere export value and delve a little deeper to look into the composition of exports, a pattern begins to emerge that poses serious questions as to the sustainability of the current export hike. The pattern referred to by the paper is a sudden emergence of two commodities—palm oil (HS 15119000) and soybean oil (HS 15079000)—as the two top export products of Nepal.

Figure 1: Nepal’s commodity export

Source: Author, using data obtained from Nepal Trade Information Portal (NTIP)

Exports of palm oil and soybean oil did not feature in Nepal’s export until 2017. But, their share in Nepal’s total export skyrocketed from 2018 (Figure 2). The prominent position of these products in Nepal’s export profile is all the more surprising given that Nepal’s production profile does not support any possibility of backward linkages (there is no extensive farming of palm or soybean in Nepal) that would have justified the export of these products. Assessment of trade data reveals that Nepal imports crude oils from third countries and exports the refined forms to India. The activity is profitable to the refineries in Nepal only because India imposes a hefty tariff on crude oils and Nepal gets duty-free access to the large Indian market for refined oils.

Interestingly, the preferential access to the Indian market for the oils refined in Nepal is secured not through Nepal–India Trade Treaty, but through the South Asian Free Trade Area (SAFTA) Agreement, which allows for less stringent rules of origin. Put briefly, while SAFTA’s rules of origin for refined palm oil and soybean oil are a minimum 30 percent domestic value-addition and a change of tariff-heading at the subheading (six-digit) level (CTSH), thereby allowing the export of these products at preferential rates, Nepal-India Trade Treaty’s rules of origin require a minimum of 30 percent domestic value-addition and a change of tariff-heading at the heading (four-digit) level (CTH), which would disqualify exports of these products at preferential rates. As rapid as the rise in the export of these commodities have been, evidence suggests that the export of these products can come down to a grinding halt any minute. India amended its imports policy to restrict the import of refined palm oil in January 2020, and Nepal’s export of palm oil collapsed after India’s change of policy. While soybean oil has stepped up to fill the gap in export created by the collapse of palm oil exports, it could very well meet the same fate if exports continue to escalate.

Figure 2: Share of soybean oil and palm oil in Nepal’s total export

Source: Author, using data obtained from NTIP

Once we deduct the export of palm oil and soybean oil from Nepal’s export, we see that Nepal’s export has in fact witnessed a significant decline since 2018 (Figure 3). Decline or stagnation in the export of Nepal’s major products is also corroborated by the fact that Nepal’s export of NTIS products—products identified by Nepal’s Trade Integration Strategy (NTIS), 2016, as major exportable products and hence worthy of receiving government’s promotion, facilitation and support—has witnessed a noticeable decline since 2018 (Figure 4).

Figure 3: Nepal’s export (with and without export of soybean oil and palm oil)

Source: Author, using data obtained from NTIP

Figure 4: Export of NTIS products

Source: Author, using data obtained from NTIP

As for the claim that Nepal’s export increased by 6.1 percent in the first six months of the fiscal year 2020/2021, it is once again largely due to the surge in the export of soybean oil. Export of soybean oil in the first six months of the fiscal year 2020/2021 increased by NPR 12.7 billion compared to the same period in the preceding fiscal year. This increase was almost large enough to counter the total collapse in the export of palm oil in the period—export of palm oil in the first six months of the fiscal year 2020/2021 was down to nothing from NPR 13.9 billion in the first six months of the fiscal year 2019/2020. There have also been some other notable increase in exports in the period. For instance, the export of large cardamom (HS 09083110) increased by NPR 2.53 billion, and export of black tea (HS 09024000) increased by NPR 1.07 billion, but on balance, the overall export in the first six months of the fiscal year 2020/2021 has increased by only NPR 4.76 billion if we are to discount the role of soybean oil and palm oil.

Furthermore, evidence shows that the rise in export of other commodities in the first six months of the current fiscal year could largely be due to the loosening of COVID-19 disruptions that had restricted exports in the preceding months. The fact that export in the last six months of FY 2019/2020 had declined significantly—by NPR 11.3 billion or 21.8 percent—compared to the same period in the preceding fiscal year lends credence to the hypothesis that the increase in exports of other commodities in the first six months of FY 2020/2021 is most likely a recuperation of lost exports during peak months of COVID-19 disruptions rather than an emergence of a persistent trend.

Hence, evidence suggests that the increase in export witnessed after 2018 is almost entirely because of the rise in the export of palm oil/soybean oil. Exports have occurred only due to the narrow window of potential created by provisions of tariff differential that exists between India and Nepal (with respect to the import of crude oil) and the provision of preferential market access to Nepali exports in India. Excluding these products that had insignificant or non-existent export before 2017 from Nepal’s export profile shows that the total export of Nepal’s other commodities has seen a decline. Furthermore, the decline in export of NTIS 2016 products is a strong indication that structural problems that hinder Nepal’s export capacity—for instance, low productive capacity, poor implementation of government’s policies and strategies, lack of coordination among government agencies, inadequate private-public collaboration and dialogue, private sector capacity constraints, issues with quality, standards, and conformity assessment (Sanitary and Phyto-Sanitary and Technical Barriers to Trade issues), the poor state of logistics, etc.—are very much intact.

Thus, the current increase in exports, rather than being a trend that can be sustained, is rather a result of a sudden surge in exports of a couple of products that Nepal has no real comparative advantage in producing. Hence, a better strategy is to address the current constraints in industrial development and export promotion rather than to revel in fluke achievements.

This article is written by Mr. Kshitiz Dahal, Research Officer, SAWTEE.